Authors note: This story first appeared in the Spring 2012 issue of the Fairhaven Free Press, which is a small student-produced publication at Fairhaven College at Western Washington University. All text and photos are by the author.

I can’t remember whether the phone call or the idea came first, but they both brought me to the same conclusion: my favorite band, Iron Maiden, would be the focus of my senior project for my degree from Fairhaven College. I wasn’t sure how I was going to achieve this goal. This story is the product of my senior project and what I learned after attending three concerts in three different countries, interviewing fans and researching one of the most influential heavy metal bands of all time.

The busy signal blared in my ear as I clutched my phone with quivering fingers. It was hard to think clearly as I hung up and redialed the radio station. I let the repetitive beeping continue for a few seconds before hanging up again. Two members of Maiden were taking questions on the radio show “Rockline” hosted by Bob Coburn on June 7, 2010.

After more than 20 attempts, I heard a ringing tone. I was talking with the producer of the show, doing my best to keep my voice calm as I explained the question I wanted to ask. The producer assured me I had a great question and told me to stay on the line.

I activated the speakerphone and set my phone near my computer before I scrambled to find a pen and paper. As the audio from the radio program played through my phone, I hastily scrawled out everything I wanted to say; I felt like all but my vital cerebral functions were about to shut down. Suddenly, I heard Coburn speak my name.

“We’ll talk to Kyler,” he said. “Welcome to Rockline. You’re on the air with us now.”

I opened my mouth and spoke to two of my heroes for the first time.

- FROM LEFT: Iron Maiden guitarists Adrian Smith, Dave Murray, and Janick Gers perform at White River Amphitheater in Auburn, Wash. on June 22, 2010.

Beginnings

I have been a Maiden fan since I was 11 when I heard “The Number of the Beast,” the band’s third album, for the first time. More than ten years later, my enthusiasm has not diminished. I designed my own degree that combined journalism, creative writing and cultural awareness and a documentary about Maiden from 2009 inspired the central idea for my senior project.

Sam Dunn and Scot McFadyen directed the film called “Flight 666” that captured a Maiden tour unlike any tour any band had ever attempted. With lead singer Bruce Dickinson at the controls, the band, 70 crewmembers and 12 tons of gear traveled in a Boeing 757 around the world. They played 23 concerts across five continents in 45 days. What I noticed about the film was, not only the balance of concert footage and interviews with the band, but also the interviews with the fans all over the globe.

Up to that point, I knew Maiden had a significant worldwide following. Seeing the documentary only confirmed that fact. For example, the band had never played Colombia before. In “Flight 666” Maiden’s manager, Rod Smallwood, said some fans had gathered near the concert venue 10 days before the show. Although the country’s military confiscated food and cameras throughout the week, fans in Colombia could not have been more excited to see Maiden.

“The world knows that Colombia has a very serious social problem, but here the metal music is alive,” a fan said in the documentary. “This is the main dream for every rocker here in Colombia. I think I’m going to cry there. I know I sound very emotional but I think I’m going to cry there because I grew up listening to Iron Maiden.”

German Quintero recalled the mayhem of trying to get tickets to the Colombia show. The vending website crashed and the phone lines were jammed moments after tickets went on sale. He was one of the campers in the days leading up to the show, having been lucky enough to get a ticket. Quintero’s efforts paid off because he managed to be front and center for the concert.

“Every song felt so perfect,” he said in an online survey. “Nothing in my life will ever top that moment. Maybe the other two times I’ve seen them after that day, but the first time was something like a spiritual experience.”

In addition to witnessing the devotion of fans all over the world, such as a man in Australia who had a tattoo of the artwork from the current tour across his entire back, fans in Argentina screaming outside the band’s hotel and the priest in Brazil who gave sermons based on Maiden’s lyrics, the documentary left me with a question. Why does this British heavy metal band, whose members are now in their fifties, appeal to people, regardless of the culture they live in? I wanted to investigate the question and seek answers from the band’s fans.

My plan was simple. I would see Maiden in Canada, the U.S. and Mexico. At each concert, I would interview fans about the band and ask them why they thought Maiden resonated with people who live in different cultures. After conducting the interviews, I would gather additional information from documentary, print and Internet sources to explain and contextualize my findings.

While the plan was simple, figuring out how to execute it was tricky. When I proposed the idea, Maiden had announced a 2010 summer tour for the U.S. and Canada, but I had no idea when Maiden would tour Latin America. I began developing questions to ask fans. The most important question being, “Why do you think Iron Maiden appeals to people who live in different cultures?” This was the question I asked two of the band members on the radio.

Background on the Band

Maiden isn’t a stereotypical heavy metal band. They never had any growling, guttural, incoherent vocals, a barrage of blast beats from bass guitars and double bass drums, or obnoxious lead guitars that shrieked relentlessly, regardless of the melodies or lyrics.

Maiden doesn’t incorporate themes of gratuitous sex or violence in their songs or concerts. The band’s lyrics have always been eloquent and complex compared to those of most rock bands.

For example, a number of Maiden’s songs tell stories from the point of view of soldiers in war. “The Trooper,” “Aces High,” “Fortunes of War,” “Paschendale,” “The Edge of Darkness,” “Mother of Mercy,” “The Longest Day” and “Afraid to Shoot Strangers” all include such a narrative.

Bassist Steve Harris and drummer Nicko McBrain produce steady rhythms, chugging like a well-tuned engine. The three guitarists, Dave Murray, Adrian Smith and Janick Gers create intricate melodies and high-energy solos over the rhythm of the songs that are both complex and distinct from what is often considered the “noise” of heavy metal. Dickinson, Maiden’s singer from 1981 to 1993 and from 1999 to present, was nicknamed “the air raid siren” when he initially joined the band because of his high-pitched screams and soaring vocals. One of the best descriptions I ever read of his vocal style is Dickinson doesn’t sing, rather he screams the lyrics with victorious cries.

Dickinson’s long hair from his early career with the band has been cut short. He is still an energetic vocalist who runs back and forth across the stage, leaping from the speaker monitors and provoking the manic energy of the audience by belting his trademark phrase: “Scream for me!” (Which is often followed with the name of the city or country of the particular show.)

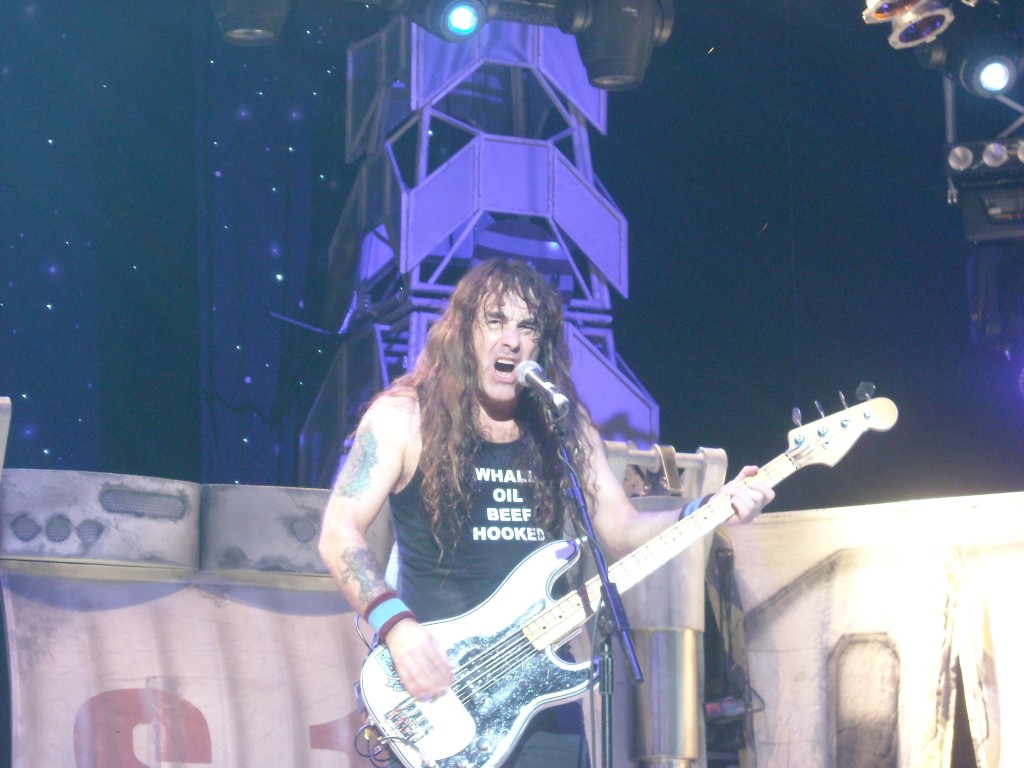

Harris crosses to each side of stage during concerts, tossing his long dark hair to the music. He deftly plucks out the beats of songs while singing, regardless if he has a mic in front of him. He aims the neck of his bass at the audience and an entire cluster of the crowd near the stage reacts, assuming Harris has pointed at them.

Murray occupies stage right. His round boyish face is framed by long hair. His foot works an array of effects pedals to adjust and warp the sound of his guitar. His fingers fly up and down the fretboard as he performs new and old songs; of the six members of the band, only he and Harris have played on every album.

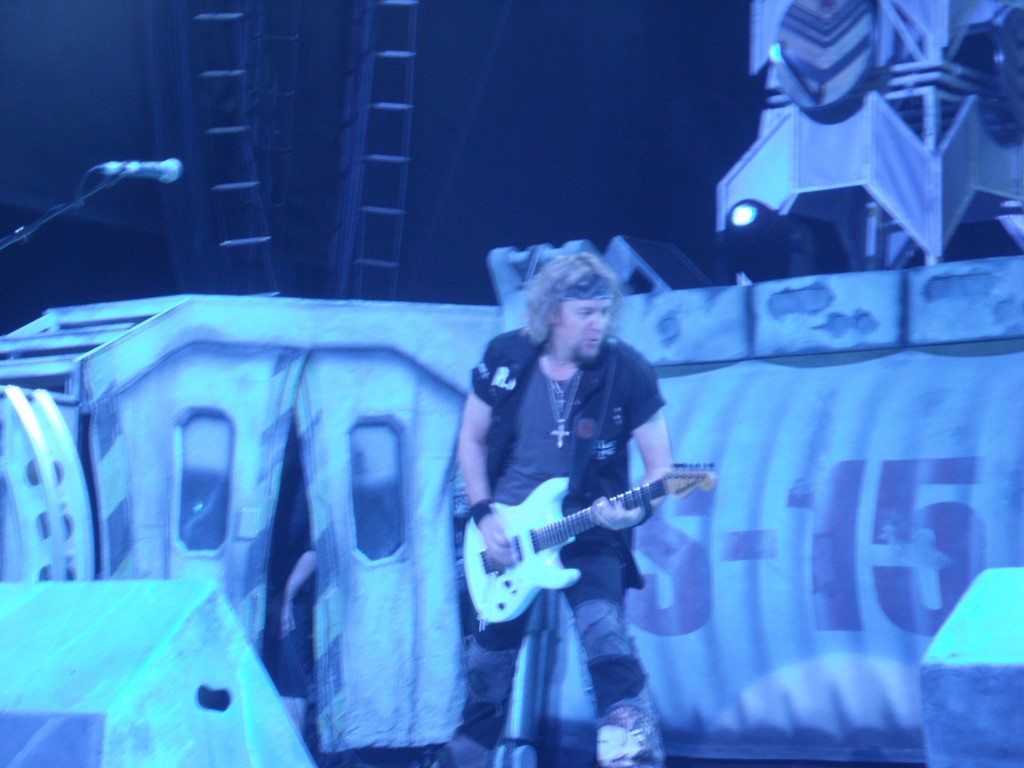

Smith stands with Murray during concerts. He often has a bandana tied around his head to keep his blond hair out of his face. He takes a meticulous and deliberate approach to playing. He appears reserved on stage compared to Harris, Dickinson and Gers, but he makes up for it with his precise handling of his guitar and solid backing vocals. He joined Maiden in 1980 after the release of the first album, which came out that year. He left the band in 1990 to pursue a solo career before returning with Dickinson in 1999.

Gers became a guitarist for Maiden after Smith’s departure and stayed on after his return. He is another energetic member of the band. He rarely stands still on his side of the stage opposite the other guitar players. He shakes his hair, kicks, twists and despite such exertion, manages to play flawlessly. Gers often throws his guitar as high as he can (and catches it) at the end of concerts.

McBrain joined the band in 1982, taking over for Clive Burr who played on the first three Maiden albums. He continued Burr’s tradition of using an elaborate drum set with lots of toms and cymbals, but only one bass drum. It is common for metal drummers to have two bass drums nowadays, but McBrain prefers the challenge of using one bass pedal.

He has a great sense of humor and meets the task of matching complex drum parts to Harris’s bass lines. McBrain has long hair, a flat nose (caused, he says, by a bully at school who punched him in the face) and a tattoo of a samurai on one arm.

Maiden has sold more than 85 million albums worldwide. According to an editorial by Vince Neilstein, who writes for the website Metalsucks.net, Maiden’s newest album, “The Final Frontier,” made it to fourth place in the Billboard charts. It’s the highest chart position any of the band’s albums have ever placed in America. Since 2000, Maiden has released four studio albums and each one has sold more than its predecessor in the U.S. Internationally, “The Final Frontier” went number one in more than 20 countries.

One reason interest in Maiden continues to grow could be because of the band’s disinterest, or at least casual attitude, toward their album sales. According to Murray in the documentary “Classic Albums-Iron Maiden: The Number of the Beast,” the band always acted on its own terms.

“We were never going to sell out and start writing songs for American radio,” he said. To this day, mainstream radio plays very few Maiden songs.

César Godino works as a software engineer in Argentina and he has been listening to Maiden for 25 years. He agreed the band has always stuck to its own vision.

“They never sold out,” he said in an online survey. “They never follow any trends. They keep on making music.”

In “Flight 666” Maiden’s producer Kevin Shirley said, “I don’t think Maiden ever cares about being relevant and I think that’s one of the things that makes them relevant.”

He continues, explaining the band belongs to Harris, who founded Maiden, and he is responsible for its direction. Smallwood agreed.

“Steve is the musical basis of Maiden,” Smallwood said in “Flight 666.” “The spirit of Maiden comes from his musical focus on what he thinks is right and he’s completely incorruptible.”

In a documentary about the making of Maiden’s fourteenth studio album, “A Matter of Life and Death,” Harris said his songwriting is influenced by what is going on in the world. The album came out in 2006 during the middle of the Iraq war and a number of the songs dealt with themes of war.

While Maiden songs are generally more complex and longer than those of other bands (the average length of the 10 songs on “The Final Frontier” is 8 minutes), they are supplemented by energetic concerts, complete with vivid visuals and theatrics.

Eddie is the zombie that graces Maiden’s album covers and the band include him at every concert. At early shows in pubs, he was a mask mounted on a board with Maiden’s logo above the drummer. When they played their self-titled anthem, “Iron Maiden,” a tube pumped red dye through the mask’s mouth to make it look like “ Eddie the ‘ead,” as he was known then, was spitting up blood.

During Maiden’s 1982 tour, they had a 10-foot tall Eddie that emerged from backstage and marched around the band members as a towering, rotting spectacle. Harris explained in the “Classic Albums” documentary that he always enjoyed making an effort to provide additional visual elements to Maiden’s performances.

In the days before large projection screens allowed fans at the back of the venues to clearly see the band members on the stage, Eddie was a great focal point that everyone could observe and enjoy.

“If you could see from our side of the fence if you like, the audience’s face lights up when Eddie comes on,” Harris said in the documentary. “It’s just the smiles on their faces and they’re just into it.”

The Seattle show

“The Final Frontier” was released August 17, 2010, about two months after the supporting tour began. The first part of The Final Frontier World Tour covered the U.S. and Canada and included a few concerts in Europe. The second part of the tour visited Indonesia, Australia, South Korea, Mexico, Colombia, Peru, Brazil, Argentina, Chile, Puerto Rico and finished in Florida. The third and final part encompassed Europe and concluded in the U.K. in August of 2011.

A little more than two weeks after talking to Harris and Gers on the phone, I traveled to the White River Amphitheater in Auburn, Wash., south of Seattle. It was a sunny day and although I arrived a few hours before the venue was even open, people were already gathering around the parking lot gates. Maiden songs blasted from car speakers. Most fans wore Maiden shirts, some smoked cigarettes or had a beer in hand and everyone was excited.

I met a group of three fans in the Muckleshoot Library parking lot, which is a near the amphitheater. As we discussed Maiden, I felt a sense of excitement and connection as I related to what they shared. For example, Kayla, 20, told me she has been listening to Maiden since she was 12 and recalled how it felt to know about the band other kids her age didn’t know existed. I had a similar attitude toward Maiden growing up because very few of my friends had even heard the band name before.

JT, 29, has been listening to Maiden for 10 years and when I asked him about why the band appeals to people in different cultures, he thought most people find elements of the music they can relate to.

“Music is music,” he said. “I mean, whether or not you understand the lyrics, you can listen to the songs, and you can get what they’re trying to say. Even if you don’t get what they’re trying to say you can still listen to how fucking awesome the guitarist is or how fucking great the drummer is or the bass player. I mean, people appreciate music regardless of what culture they’re in.”

I remember listening to Maiden songs again and again, doing exactly what JT described by focusing on a specific instrument. I’d dissect the beat in my head, identifying an extra hit on the snare drum in “The Number of the Beast” or the seamless transition from the first guitar solo to the second solo in “The Trooper.”

I met a father and his two sons near a parking lot gate. On of the sons Brad Allison, 20, said people around the globe are excited by Maiden’s musical reputation and commitment to their stage production.

“No matter what country you go to whether it’s Croatia or Brazil or the United States or England, I mean, everyone across the world knows what Iron Maiden is about,” he said. “Iron Maiden, above all, knows how to put on a fucking show. Music is just the universal language.”

The father, Tim Allison, 43, added that everyone needs to take a break and Maiden gives their fans concerts to look forward to. When I asked about any songs or lyrics the group appreciated, Tim mentioned how “Run to the Hills” commented on the destruction of the Native American nation by the U.S. government. He said it is an important topic for people to remember so something that awful won’t happen again.

Brad brought up the anti-war sentiments expressed in songs such as “Two Minutes to Midnight,” “Paschendale” and “The Legacy.”

“[Those songs] don’t have to conform to anything else that’s going on, they don’t have to sing about the specifics, they can tell a story and promote that anti-war feeling. Not that, ‘oh this war is bad,’ but show the consequences of what’s going on,” he said.

I agree with Brad that although Maiden songs about war don’t convey explicit condemnations of military conflicts, Dickinson has said otherwise during concerts. He introduced the song “Afraid to Shoot Strangers” in 1992 at the Monsters of Rock Festival in England with the following explanation.

“[This song] was written about the people that fought in the Gulf War. It’s a song about how shitty war is and how shitty war is that it’s started by politicians and has to be finished by ordinary people that don’t really want to kill anybody,” he said.

Soon after finishing the interview with the Allisons, the gates opened and my cousin, her husband and my mum, who had come along to see her first rock concert, parked and ran to get in line. I bought a few Maiden T-shirts to add to my collection (I have more than 50 now).

Once I got into the venue, I headed for the pit area, hoping to get as close as possible to the band. The sun was still up and most people were visiting the concession booths or heading for the beer gardens. I passed on buying beer ($9 for a can!).

The opening band, Dream Theater, played six songs and lured people to the pit and their seats. By the time they finished, the sun was setting. Crewmembers swarmed the stage to set up Maiden’s gear.

I stared up at the massive lighting trusses and speakers suspended from the amphitheater roof until the show began. As the main lights over the stage dimmed, the audience roared with excitement. People behind me surged forward and crushed my pelvis into the steel railing as music blared through the PA.

Lights flashed in time with orchestral blasts—pools of white, blue and purple light materialized on the stage and red LED bars created a crawling effect across the trusses. At the crescendo of the galactic introductory score, a black drape fell to reveal a star-studded backdrop and Maiden took the stage as Smith played the opening notes to “The Wicker Man.”

Although he’s nearly impossible to see behind the drums, McBrain announced his presence with appropriate thuds on the bass drum and toms behind Smith’s guitar. As the first verse of the song approached, Dickinson ran out from backstage, mic in hand. He leapt onto the drum riser and landed as his voice soared over the music while the crowd enthusiastically chanted the lyrics with him.

Of the 16 songs Maiden played, 11 of them were from the four most recent studio albums. It didn’t matter if a song was a classic from the 1980s or, in the case of “El Dorado,” a new song made available online for free only two weeks previously.

The band paused after the first three songs of the set to allow Dickinson to welcome the fans to the show and talk about the forthcoming album. He explained that because “The Final Frontier” wouldn’t be out until August, “El Dorado” was the only song the band would play from the new album.

I downloaded “El Dorado” and listened to the nearly 7-minute track 30 times the first night I had it. As I focused on the lyrics, I realized the song was about financial crises. Not only did the song have a catchy galloping bass line, it was, in true Maiden form, addressing important and topical issues. “El Dorado” was composed during the current global recession. In the U.S., the housing crisis was a significant part of the economic downturn. In a clip posted on the music news website Roxwel, Dickinson recalled when similar catastrophes gripped the U.K. in the past and how that inspired him to write the lyrics for the song.

“All these people bought houses thinking, ‘houses are going up. Just buy a house. It’ll always go up. Endless growth, nothing can stop it,’” he said. “And you get this kind of casino thing, people play the casino with their lives.”

“El Dorado” explores notions of financial idealism and manipulation. Dickinson described the song as a timeless tale of deception. As he talked, he adopted the hypothetical role of a cruel affluent person, narrating his exploits achieved at the expense of the less fortunate.

“The guy’s sailing away in his boat,” he said. “‘Here you go guys. Every man has a canoe. I’m the only guy that’s got the paddle. Did I tell you that? No, sorry.’”

The concert at the White River Amphitheater concluded with an encore of three songs, two from Maiden’s third album and one from their first album. My hips were sore from being shoved into the barrier for the length of Maiden’s set. The band threw their guitar picks, wristbands, some drumheads and drumsticks to the crowd. One of the personal highlights of the evening was when I caught a drumstick.

The Vancouver B.C. show

Two days later, my parents, brother and I headed to Vancouver B.C. They dropped me off outside General Motors Place where a couple Maiden merchandise booths were set up.

I was confused because there wasn’t a large crowd, which seemed odd because I knew the show was sold out. The sounds of cars, elevated commuter trains and shouts from ticket scalpers filled my ears as I searched for fans to interview.

I talked with Carson, 18, who had been listening to Maiden for about five years. He discovered the band right when he started to play bass guitar and he recognized how much he appreciated music.

“To me, music just makes you feel better no matter your emotions, right?” he said. “Maiden was just there. If I was having troubles at home and school or shit like that, Maiden was the thing that got me away; took me to another place.”

Carson said people in Central and South America probably don’t see a lot of major bands that tour worldwide in their countries, which could explain why they are more passionate and excited when bands like Maiden come to perform. He added that Maiden’s influence on the genre of heavy metal is based on the band’s ability to produce quality songs that people appreciate.

“Iron Maiden is just one of those bands that has always defined metal,” Carson said. “They’ve always had great records, great songs at the time and everyone just seems to really enjoy it.”

Although most people wear Maiden T-shirts to shows, I met Felipe, 23, who was clad in jeans and a yellow shirt with the flag of Brazil splashed across the chest. He’d been listening to the band for about six or seven years. Felipe likes the composition of Maiden’s songs; they rely on simple elements to make complex arrangements using precise instrumentation and poignant lyrics.

“They talk about relevant stuff,” he said. “They talk about wars and history, it’s not just writing about any shit and playing it. They have something to say and it sounds great.”

Felipe also offered some insight about the band’s popularity in Brazil. He mentioned that in the past, most metal tours didn’t come through countries in South America. Since more bands have started touring there, it has excited thousands of people who turn out for concerts.

Once I finished my interviews in Vancouver B.C., people were filling the plaza in front of the venue. When the doors swung open, I bolted for the barrier in from of the stage.

Soon after I picked my spot at the steel railing, more people began pouring into the venue. No band was on the stage, but the crowd pushed me into the barrier as if there were. The house lights still lit the arena and the energy of the audience was noticeably elevated compared to the Seattle show. Periodically someone would begin chanting “Maiden, Maiden, Maiden!” and others in the vicinity would join in.

I wore nearly the same outfit as the previous show—high-top Converse, denim cutoffs, a Maiden bandana, denim vest with Maiden patches and buttons and the obligatory Maiden shirt. I could feel my clothes sticking to me with sweat at the end of Dream Theater’s set, giving new meaning to the phrase “warm-up act.” If this crowd was this excited about the opening act, what was going to happen when Maiden took the stage?

I only caught glimpses and a few of the opening notes to “The Wicker Man” because the force of the crowd bent my upper body over the railing and the yells of approval from the audience drowned out the music. People around me were jumping up and down, headbanging and jutting their arms in the air. I straightened up just as Dickinson ran toward the audience before launching into the lyrics. The crowd surged toward him, crushing me into the barrier again.

In keeping with the galactic theme of “The Final Frontier,” the set was designed to look like the inside of a space station. Metal grating and catwalks ran around the sides and rear of the stage. Two towers, containing additional lights, stood at the corners of the catwalks. The stage was covered with a linoleum floor, printed to look like more steel grating.

At both the Seattle and Vancouver B.C. shows, the band gave Dickinson a chance to talk to the audience half way through the concert. A little more than a month earlier, heavy metal frontman Ronnie James Dio passed away. The former singer of Black Sabbath had been an inspiration for Dickinson and a good friend to everyone in Maiden. At both concerts, the audience began chanting “Dio” repeatedly after Dickinson said his name. He had to wait for the crowds to quiet down in order to finish his announcement, which was the band wished to dedicate the next song, called “Blood Brothers,” to Dio.

Harris, who writes most of Maiden’s material, composed the song for his father after he passed away while Harris was on tour. It has a few heavy moments, but contains quieter passages as well. In the bonus features of the “Iron Maiden: Rock in Rio” concert DVD from 2002, Dave Murray discussed the song.

“‘Blood Brothers’ I think is a great song to play because there’s so many different time changes. There’s a very heavy, up-tempo theme, clean, melodic stuff,” he said. “That kind of represents a small picture of Iron Maiden.”

When Maiden’s encore began, the crowd started churning like spooked cattle. A mosh pit formed about 20 feet back from the barrier. I managed to stay clear of the whirlpool of bodies, but I had already sustained minor injuries.

My neck was sore from headbanging and I had dark bruises on both of my hips from where they had been continually smashed into the steel barrier both this night and from Seattle. I wasn’t sorry when I left the venue, though. The show had been a great experience because not only had Maiden put on another spectacular show, but the audience had been loud, energetic and responsive from start to finish.

I drifted outside to meet my family. When the cool night air enveloped me, I realized the sweat I’d first noticed during Dream Theater’s set had multiplied. My vest was soaked, patches of my cutoffs were drenched and my hair was plastered to my face and neck. Brilliant!

The Mexico City show

In November 2010 I received the news I had been waiting for. Maiden announced the second part of “The Final Frontier World Tour.” The band would be rolling out the 757 airplane, named “Ed Force One,” again and traveling in a similar fashion to the tour captured in “Flight 666.”

Tickets for the show went on sale a couple weeks later and Mexico City was on the tour. The show was scheduled for March 18, 2011, which fell right on my spring break. I had already bought my airline tickets and placed my trust in members of the Iron Maiden Fan Club to help me out. Although I had never attended a Fan Club Meet-up, I soon discovered fans in Mexico City had organized one at the local Hard Rock Café. I sent out a message on the Club’s forum that explained my project and my desire to have some place to stay in Mexico.

A woman named Ligia responded. She kindly welcomed me to crash at her place and take me to the Meet-up. “Iron Maiden: Rock in Rio” was the first Maiden DVD I ever bought. In the bonus features I noticed how the band members acknowledged the importance of the fans and their loyalty.

“You couldn’t do this without the fans,” Murray said. “They’re putting you where you are, so we’ve always maintained that kind of street-level thing where we’ll go out there and sign autographs, even if there’s 50 or a hundred of them. I think that’s all part of it. They give you so much. I wouldn’t change it at all.”

I learned in Mexico that the loyalty of Maiden fans to the band is matched only by their loyalty to each other. Ligia not only gave me a place to stay, she also introduced me to a number of local Maiden fans and told them about my project.

Two cover bands played at the Meet-up, Iron Kidz and Iron What?, took command of Hard Rock Café, performing both new and old Maiden songs. They even had a full backdrop for the stage, featuring Eddie in his most recent incarnation from “The Final Frontier” album cover as a snarling, drooling alien.

Two of the guitarists from Iron Kidz, whose members are all in their early teens, remained on the stage after their set to play with Iron What? I was blown away by the musicianship of both bands, and especially impressed with the singer of Iron Kidz who dressed just like Dickinson on the current tour, right up to the Eddie-emblazoned beanie.

It turned out my brother was in Mexico City for a business trip at the same time and so I managed to rendezvous with him and his business partner. The three of us went out to the concert venue the day before the show. Foro Sol is a huge baseball stadium, but the staff rolls back the field and sets up a large stage at one end of the massive arena for concerts. A racecar track and other sports fields surround the venue.

I met Mario Martinez, 18, outside the stadium. He explained that Maiden crosses cultural boundaries with their music.

“People in India who like Iron Maiden are like people who like Iron Maiden in Argentina,” he said.

He also commented on the stories expressed in the lyrics. He compared them to a novel and their ability to take listeners on journeys.

As we were driving away, I saw a small group next to a gate outside the venue. We stopped and within a few moments of speaking with them, learned they were staying the night in line. David Gama, 20, expressed his respect for Maiden.

“I listen to a lot of metal bands but Iron maiden is the only I’ll pay to see,” he said. “The first time I saw them, I cried.”

Daniel Galuán said Maiden appeals to different cultures because of their lyrics and their aggressive sound.

The next day, my bother and his business partner drove me to the show. Beneath an elevated commuter train line, I saw tents of bootleg Maiden merchandise. People swarmed the booths, swapping their current shirts for new purchases. The tents stretched for at least four blocks. We drove around to the other side of the venue where I met up with Ligia and my new friends from the Meet-Up. I had been lucky enough to win a wristband through the Fan Club that allowed me early entrance to the show. At the main gates, throngs of fans were already chanting Maiden’s name repeatedly.

Once in the arena, I ran toward the stage. Within minutes, the pockets of my cutoffs were inaccessible; the crowd pressed me tightly against the barrier. It was 4:30 p.m., nearly 80 degrees and Maiden wasn’t going to start playing until 9:00 p.m. Not even an hour had passed before the members of the security team had to lift a woman out from behind the barrier because she was suffering from heat exhaustion.

It seemed like every few seconds a new voice was yelling for water. I glanced over my shoulder and watched as vendors pushed their way through the audience, while supporting trays of snacks and beer. At one point, people seized one of the trays and a shower of beer spilled over everyone nearby.

As the sun began to set, the opening band, Maligno, started their set. I looked behind me and saw the stands at the back of the venue filling with people. The entire space usually occupied by a baseball field was full of fans. When Maligno finished, Maiden’s crew began preparing the stage.

As 9:00 p.m. ticked closer, the crewmembers encouraged the crowd by holding open palms next to their ears. I roared my approval with everyone around me. An eerie, bellowing cacophony of shouts of the estimated 50,000 attendees echoed through the stadium as the song “Doctor Doctor” by UFO blared forth, replacing the opening orchestral score from the previous part of the tour.

As the song concluded, all the lights switched off and the two screens on both sides of the stage lit up with a flashing animation sequence, full of lightning, stars and planets. The heavy bass and thudding drums of “Satellite 15…The Final Frontier” chugged in time with the images. The alien Eddie appeared on the screens and another collective cry of delight rose from behind me.

Dickinson’s voice burst through the PA and the starry backdrop blinked to life. The crowd began wailing along to the lyrics. As the ending of the first part of the song approached, I saw the band members take the stage—a sudden pause, an absence of amplified noise.

McBrain struck his snare with a resounding crack and the song continued as white light illuminated the stage. Dickinson periodically held his mic toward members of the audience and they shouted the lyrics in earnest. Shoulders knocked into mine as the current of the crowd pushed me left and right.

Smith held the last note of the song and McBrain began a gentle clicking roll on his hi-hat cymbals, signaling the beginning of “El Dorado.” The sound of guitars flared as Dickinson provoked the crowd.

“Let me see your hands, Mexico City!” he shouted. “Scream for me, Mexico!”

Maiden followed “El Dorado” with “Two Minutes 2 Midnight” before playing two songs off the new album. The crowd clapped and sang along with every song. Whenever the band wasn’t playing, the audience directed chants of “Maiden!” at the stage.

When Harris and Gers began jumping up and down while playing “Dance of Death” and “The Wicker Man,” I had no choice but to mimic them; the bodies hopping next to me were lifting me off my feet.

In “Flight 666,” Dickinson commented about the passion of Latin American audiences.

“You know they’re going to be great. The anxiety is, are we going to be as good as the audience?” he said. “We’ve really got to deliver a passionate performance that justifies our existence in front of this audience.”

Smith said in the documentary that the members of Maiden came from the working-class area of London, which he think adds to the band’s credibility with audiences all over the world, especially in Latin and South America.

“It’s like playing to a soccer crowd,” he said. “They’re singing, they’re chanting all the words and it’s a real tribal thing.”

At one point in the documentary, members of the audience in South America lifted a banner that read, “Iron Maiden is my religion.”

After playing “The Wicker Man” in Mexico City, Dickinson spoke to the crowd again with a similar attitude to how he addressed the fans in Seattle and Canada. He was introducing “Blood Brothers,” but this time, the band dedicated it Maiden fans who were facing difficult times in certain parts of the world.

Dickinson mentioned the earthquake that shook Christchurch, New Zealand, killing 185 people when Maiden had been nearby in Melbourne, Australia. Before the band came to Mexico, they had two shows scheduled in Japan. “Ed Force One” was eight minutes from landing when reports reached the aircraft about the massive earthquake and tsunami that devastated the country. Both of the shows in Japan were canceled. Maiden wound up selling the Japan event shirts online to benefit the country and raised more than $60,000. Dickinson also commented on the conflicts in Libya, Egypt and violence throughout the Arab world.

“[This song] goes out to everybody because it doesn’t matter what religion you are, it doesn’t matter what color you are, it doesn’t matter whether you’re male or female. If you’re an Iron Maiden fan, you’re blood brothers!”

After Eddie made his appearance on the stage during “The Evil That Men Do,” the audience screamed their approval by yelling Eddie’s name and the familiar chant in Latin America: “olé, olé, olé, olé! Maiden, Maiden!”

The encore included the same songs from the Seattle and Vancouver B.C. shows: “The Number of Beast,” “Hallowed Be Thy Name” and “Running Free.” Everyone around me shouted the lyrics and I was getting bent over the barrier as I had been in Canada. Harris and Gers sprinted across the stage during the solos of “Hallowed Be Thy Name.” Dickinson acted as a composer for the crowd’s thundering yells, before he sang the closing lyrics to the song. During “Running Free,” he introduced the members of the band and threw his sweat-soaked beanie into the audience.

At all the shows, I noticed how the band members maintained eye contact with the crowd. In a CNN Revealed special, with aired in 2008, Dickinson explained the importance of the way Maiden relates to their fans during concerts.

“You have to look them in eye with a fierce engagement, so they know it’s real and it’s not mucking about,” he said.

He added that it’s important to create a space at Maiden concerts where the members of the audience “feel safe to go absolutely bonkers.”

The Maiden family

Although I didn’t get to interview as many fans as I’d hoped at the concerts, I received a lot of great feedback from the online surveys. A few people mentioned the way Maiden’s music transcends cultural boundaries. Alastair Hastie, 21, from the U.K. thought people admire the band because neither advertising campaigns, nor mainstream music companies, support it.

“[Maiden] went by the power of the music alone and this kind of conviction can be understood on a global level,” he said.

David Besten, 23, is a student in Holland and commented the topics Maiden explores resonate across cultural divides.

“[The] themes in their songs, for example, history, war, death, life, love, fear and hope are recognized by people from different cultures,” he said. “Furthermore, Iron Maiden cares about their fans and never lets them down.”

Chris, 41, from Canada explained that not only are the song topics relevant, but also the stories told in the lyrics, which come from shared human experience.

“Someone in Mexico can relate to feeling ‘your neck skin crawl/When you’re searching for the light’ the same as someone in Canada,” he said, referring to lyrics from the song “Fear of the Dark.”

A composer and music teacher from Sweden named Fredde Uhlmann, 40, mentioned the significance of Maiden’s concerts.

“They’re an incredibly good live act,” he said. “[Maiden] always had their main focus on the music and to deliver a good show.”

His point of view is similar to Brad Allison’s ideas about the band’s commitment to their live performances.

One of the highlights of Maiden’s shows, no matter what songs they play, is the appearance of Eddie on the stage. In addition to asking about why Maiden resonates with people regardless of what culture they live in, I wanted to find out what fans think about the band’s mascot.

“Eddie is fucking great,” JT said. “The key to putting together a good band is to have music girls can dance to and fucking awesome things guys care about like zombies bursting out of the ground with lightning hitting them.”

I attended an Occupy Wall Street protest in Seattle last October and I met Marc who had just flown in from the U.K. The sign I carried was written in Maiden’s font, which caught Marc’s attention and we talked for 45 minutes about the band.

“When Eddie comes out, whether it’s a 50-foot guy with flames on his legs, everyone goes ‘that’s what we are here for.’ For a show, for something that’s earnest and a band that respects their fans,” he said.

Zoe, 20, from the U.K. responded to my questions online. She commented that the image of Eddie was important to Maiden’s success.

“In a lot of cases, the artwork is what inspired people to first listen to them,” she said.”

Fans relate to Eddie in a number of different ways. When I interviewed Christian Norp, 19, at the Seattle concert, he said Eddie is like a rock father figure he never had. Chad Cooper, 41, from the U.S. said Eddie is a representation of the intensity of Maiden’s music.

Nicko Dehanie, 39, explained Eddie serves as a sign to other fans; those who wear Eddie on their shirt or on their skin indicate they belong to the Maiden family. The various incarnations of Eddie on album covers and at concerts reveal his changing nature that allows fans to see him any way they want. For this reason, Eddie provides another way for fans across the world to be excited about Maiden.

During the CNN Revealed special, Harris and Dickinson briefly discussed the band’s mascot.

“Eddie is everything we don’t want to be,” Harris said.

“He’s the most outrageous and biggest rock star there’s ever been. And it’s great because it means that we don’t have to be,” Dickinson said.

I think this is an important point because it reveals the boundary the band members have drawn between their private lives and their lives in Maiden. They took care of themselves physically and mentally, rather than adopt the legendary, perhaps stereotypical, rock and roll lifestyle. It is likely one of the reasons they are still producing quality music and touring.

In the special, Dickinson also pointed out the difference he feels when he performs live versus when he’s flying airplanes. Everyone would be terrified if Dickinson the Maiden singer were at the controls of “Ed Force One” rather than Dickinson the pilot.

“There’s a different kind of thing about being on stage where everything is about drama,” Dickinson said. “Flying an airliner, everything is about trying to prevent drama.”

Maiden has been together for more than 30 years and they have grown close to members of their crew as well as each other. Dehanie mentioned the Maiden family, which is a concept the band discussed at the end of the documentary “The History of Iron Maiden Part 2.”

McBrain mentioned how the members of the band, the crew and the music business are all friends.

“A lot of people go ‘you can’t be friends in business,’ which is a load of bollocks, basically, especially in our business, in Iron Maiden’s family,” he said.

“There’s a lot of competence and heart that’s required to be part of the Iron Maiden team and it runs right through,” Smallwood said in the documentary. “It’s why we’ve got people in the crew like Dougie Hall, the sound man, for 25 years now.”

The sense of belonging isn’t limited to just the band and crew. At the Seattle show, Dickinson commented that there are music fans, then there are heavy metal fans and then there are Iron Maiden fans.

He asked members of the audience who were seeing the band for the first time to raise their hands. Dickinson then welcomed those whose hands were up to the Maiden family.

Ligia said she’s met some of her best friends at Maiden shows. Kyle Fletcher, 41, from the U.S. suggested some Maiden fans relate to the band members more like friends, rather than considering them to be elite rock stars. When she recounted the emotional experience of finally being at the barrier at Maiden show in 2010, Nanette, 45, from the U.S. also recognized friends she has made through the common interest in the band.

“I have truly met some of the best people I have ever known from all over the world because of Maiden,” she said.

Along with the global community of fans united by Maiden, it’s important to keep in the mind the impact the band has on an individual level.

“Maiden has gotten me through a lot of tough times growing up and over the years,” Nanette said. “[Maiden’s] something that really does bring joy into my life. My heart beats faster and I get a huge smile on my face and start rockin’ out!”

Paulina, 41, from Sweden explained that she was hospitalized for a couple months in 1989 and Maiden kept her spirits up.

“Listening to the lyrics, the layers in the music, the energy and the eeriness made me focus on other things than the damages my body had been put me through,” she said. “It saved my life, first and foremost mentally, but also physically.”

She also discussed the benefits of attending concerts in other countries.

“To travel to see your favorite band in so many different cultures enriches your soul and feeds your mind and broadens your perspectives.”

I had heard and seen the energy of Latin American audiences in DVDs, but the experience of actually being at the show in Mexico, like the people I met there, are unforgettable.

In response to my question on the radio, Harris replied: “I think music is, in general, universal anyway. I think if you’ve got good strong melody lines, I think it doesn’t matter so much—words are important but I think it doesn’t matter so much—if people know what the words are when they first hear the song then they get into the words afterward. So I think if you’ve got strong melody lines, that’s the key really. That’s my theory anyway.”

In addition to Brad Allison, other fans noted the universal element of the band’s lyrics and music.

“[Maiden’s] lyrics and stories aren’t that culture-tied,” Taneli Teelahti, 20, from Finland said. “They don’t represent one culture and one point of view, but are instead quite versatile, universal and wise.”

Harris’s reply explains part of the band’s global appeal, but I think fans also recognize the genuine enthusiasm and dedication Maiden brings to their music and concerts. For me, the artwork and music are what initially drew me to the band. Since then, as I have learned more about the band members and who they are outside of Maiden, my respect for them has grown.

I spoke with Kevin Fitzgerald, a graduate teaching assistant with Western Washington University’s history department, who studied how members of metal audiences form communities through participation at concerts. He began listening to heavy metal more when he started studying sociomusicology, a discipline that examines the social context of music. Fitzgerald is interested in exploring how music transcends social and cultural boundaries.

In 2009, he traveled to Slovenia to attend the weeklong music festival Metalcamp where he studied the community ethics of the audience. One ethic that emerged was members of the crowd singing with the bands or singing with each other.

“Sing-alongs seemed to be important,” he said. “That seemed to be a way that people practiced this ethical construction and also performed it.”

Singing the same songs established a sense of relatedness and an expectation of behavior between friends or fellow concertgoers who were there to have a good time.

Fitzgerald also witnessed drunken men wrestling each other in the mud and although there were no sinister intentions behind such exchanges, he thought the activity reflected the ethics of the mosh pit.

“People helping each other out while smashing into each other kind of thing,” Fitzgerald said. “We should be releasing all this energy and having this good time, but we should be safe about it and take care of each other at the same time.”

I asked Fitzgerald what sets crowds at metal shows apart from other audiences.

He said the emotional energy and enthusiasm are more intense and fueled by the brutal sound from the bands.

“There seems to be, in connection with the exhilarating aspects, a social catharsis,” he said. “It’s a form through which people can get an emotional release and that can actually have benefits to mental health on a pretty large scale.”

He added that when most psychologists claimed metal was bad for children, a couple said it could just the opposite because of the expressive outlet it provides for youth.

When Dickinson described the need for an audience to feel comfortable going “bonkers,” another way to say it is Maiden makes an effort to ensure the members of their audiences feel free to fully express themselves.

Maiden caught Fitzgerald’s attention because the worldwide enthusiasm during the 2008 tour. The footage from the Colombia show surprised him and he found himself singing along to “Run to the Hills” with the crowd. I asked Fitzgerald if he recognized anything while watching Maiden’s performance that reminded him of his research.

“The kid playing the air drums right up in the front, which just sticks in my mind and it seems like such a good example of audience participation,” he said. “There’s this feedback even though the band’s 10 feet up and 20 feet that way, there still seems to be an intense connection, especially with the people up front and the band.”

He also noticed the persona the members of Maiden have adopted in order to better relate to the audience.

“They clearly didn’t just come with this in the last couple years, this is something they’ve been refining for decades and that really shows,” Fitzgerald said.

He identified the gestures Harris makes at the audience—beckoning with one hand while playing his bass with the other—as a specific example of the relationship Maiden has created during their performances. Eddie represents another part of the band’s persona and Fitzgerald gave me one of the most compelling interpretations of the band’s mascot I heard during the entire project.

According to Fitzgerald, Maiden, along with some other metal bands, seems to communicate a post-structuralism critique of the world’s political economy.

“There’s a recognition of a society built on rational economic forms that is decaying,” he said. “There is something beyond that decay that is ominous. There’s an ominous presence that the direct economic problems are just the surface of something far more ancient and problematic that looms over humanity.”

He tied this idea to the false promise of modernity, which is trying to counter the social decay. Political, economic and environmental betrayal weakens society and the concept of modernity. Fitzgerald interpreted that bands like Maiden are commenting on these failures with their music. Skeletal figures, such as Eddie, could represent the ominous beyond or the decaying systems humanity has constructed.

A Maiden song, called “Virus,” has a line: “Watching beginnings of social decay.”

“A lot of metal bands bring this idea of humanity as a whole, that we’re all prone to the same nuclear holocaust,” Fitzgerald said.

Reflection on the project

After interviewing Fitzgerald and some of the band’s fans, I have gained a better understanding of the global unity Maiden helps create.

In her book, “Heavy Metal: A Cultural Sociology,” Deena Weinstein wrote that the ongoing appeal of heavy metal depends on the relationship between the fans and the bands.

Maiden is no exception. The sing-alongs Fitzgerald mentioned, and the call and response between the audience and the band discussed in Weinstein’s book, create a community. Crowds expect to hear Dickinson’s phrase— “Scream for me!”—and to see Eddie at Maiden’s concerts.

The members of Maiden made it a priority to develop the performance persona Fitzgerald discussed. Their relationship with audiences boosted their popularity around the world, along with the appeal of their music, lyrics and Eddie.

At the end of “Flight 666,” Dickinson discussed the worldwide following of the band.

“All people need is something to hang onto that’s real. That somewhere there’s something in the universe you can rely on that won’t let you down. And if Maiden fulfill that for people, I think that would be a remarkable thing. We might all end up retiring at some point in the future having actually achieved something,” he said.

Before doing this project, I thought the “we” referred to the band. After researching Maiden and heavy metal, as well as hearing feedback from fans from multiple countries, I suppose the “we” could also refer to all the members of the Maiden family.

I gave a presentation about my experience with the project as well. It can be viewed here